The Indian Railways runs more than 12000 trains between 8000 stations covering a distance of 120000 Kms. It carried 8 billion people in 2019 with 9000 trains running each day, moving people and freight to all corners of the country.

Why is modeling the train routes an interesting exercise ?

Finding all the trains travelling between a pair of stations is a classic graph search problem, traditionally not a strong suit of relational databases. In this series of blog posts I explore how to model train routes in a relational database.

The data

The dataset used is the 2017 railway timetable provided by the Open Government Data Platform of India.

All the code (including the dataset) can be found here. I fixed a few rows in the original CSV that were badly formatted, so take the data from here and have a Postgres database up and running if you want to follow along by running the SQL statements in this blog post.

The dataset contains one row for each station along a train’s route with other information like the arrival and departure time and the distance travelled.

Let’s load this csv to a table so that we can take a better look at the data.

CREATE TABLE staging_trains

(train_no integer,

train_name text,

seq smallint,

station_code text,

station_name text,

arrival_time time without time zone,

departure_time time without time zone,

distance smallint,

source_station text,

source_station_name text,

destination_station text,

destination_station_name text);

\copy staging_trains from 'Train_details_22122017.csv' csv header;

The column train_no is a unique identifier for every train and is a good candidate to be the primary key while train_name is the corresponding user friendly name.

The column seq gives the ordering of the stations on the train’s route. It is a number starting from 1 and monotonically increasing.

The information of each station on the route is given by station_code and station_name columns.

arrival_time and departure_time are self describing.

The column distance is the cumulative distance travelled by the train to reach the station. So it makes sense that when seq is 1 the distance is 0.

The columns source_station/source_station_name and destination_station/destination_station_name are the origin and final stations for the train.

Before we normalize

All tables in our database should address a single subject and we should not have redundant data i.e. the same piece of information in multiple places.

The staging table breaks both these rules.

select * from staging_trains order by train_no, seq limit 8;

train_no | train_name | seq | station_code | station_name | arrival_time | departure_time | distance | source_station | source_station_name | destination_station | destination_station_name

----------|--------------|-----|--------------|--------------|--------------|----------------|----------|----------------|---------------------|---------------------|--------------------------

107 | SWV-MAO-VLNK | 1 | SWV | SAWANTWADI R | 00:00:00 | 10:25:00 | 0 | SWV | SAWANTWADI ROAD | MAO | MADGOAN JN.

107 | SWV-MAO-VLNK | 2 | THVM | THIVIM | 11:06:00 | 11:08:00 | 32 | SWV | SAWANTWADI ROAD | MAO | MADGOAN JN.

107 | SWV-MAO-VLNK | 3 | KRMI | KARMALI | 11:28:00 | 11:30:00 | 49 | SWV | SAWANTWADI ROAD | MAO | MADGOAN JN.

107 | SWV-MAO-VLNK | 4 | MAO | MADGOAN JN. | 12:10:00 | 00:00:00 | 78 | SWV | SAWANTWADI ROAD | MAO | MADGOAN JN.

108 | VLNK-MAO-SWV | 1 | MAO | MADGOAN JN. | 00:00:00 | 20:30:00 | 0 | MAO | MADGOAN JN. | SWV | SAWANTWADI ROAD

108 | VLNK-MAO-SWV | 2 | KRMI | KARMALI | 21:04:00 | 21:06:00 | 33 | MAO | MADGOAN JN. | SWV | SAWANTWADI ROAD

108 | VLNK-MAO-SWV | 3 | THVM | THIVIM | 21:26:00 | 21:28:00 | 51 | MAO | MADGOAN JN. | SWV | SAWANTWADI ROAD

108 | VLNK-MAO-SWV | 4 | SWV | SAWANTWADI R | 22:25:00 | 00:00:00 | 83 | MAO | MADGOAN JN. | SWV | SAWANTWADI ROAD

This table combines two pieces of information in each row - the source and destination of a train as well as the information of an intermediate stop. We also have duplicated data as seen in the columns station_name, source_station_name and destination_station_name.

Duplicating data opens the door for discrepancies to creep in and we see this in the very first row above. The columns station_name and source_station_name hold slightly different values - SAWANTWADI R vs SAWANRWADI ROAD - even though both use the same station code value.

Modifying redundant data is another challenge. Consider what happens if we have to update the name of a station - we would have to find all the rows with that station code/name in either of the three columns and update them.

Let’s remove the redundant station names by extracting all the station codes and names to a new table - whenever we have a station code with different data in the name column we will take the longest string on the assumption that longer name is better.

CREATE TEMP TABLE all_stations AS

SELECT station_code, station_name FROM staging_trains

UNION

SELECT source_station, source_station_name FROM staging_trains

UNION

SELECT destination_station, destination_station_name FROM staging_trains;

CREATE TEMP TABLE all_stations_ranked AS

SELECT station_code,

station_name,

rank() OVER (PARTITION BY station_code ORDER BY length(station_name) desc) AS r

FROM all_stations;

CREATE TABLE stations AS

SELECT station_code, station_name FROM all_stations_ranked

WHERE r = 1;

ALTER TABLE stations ADD PRIMARY KEY (station_code);

ALTER TABLE stations ALTER COLUMN station_name SET NOT NULL;

NOTE - I choose not to introduce a surrogate key in the stations table as all our queries will specify the station codes directly.

With that out of the way, we can now get down to the job of splitting the original data into two tables - one for each train and the other for all the stations on a train’s route.

CREATE TABLE trains

(train_no integer PRIMARY KEY,

train_name text NOT NULL,

source_station_code text NOT NULL REFERENCES stations(station_code),

destination_station_code text NOT NULL REFERENCES stations(station_code));

CREATE INDEX trains_source_station_code_idx ON trains(source_station_code);

CREATE INDEX trains_destination_station_code_idx ON trains(destination_station_code);

INSERT INTO trains

(train_no, train_name, source_station_code, destination_station_code)

SELECT distinct train_no, train_name, source_station, destination_station FROM staging_trains;

CREATE TABLE train_stations

(train_no integer REFERENCES trains(train_no),

seq smallint,

station_code text NOT NULL REFERENCES stations(station_code),

arrival_time time without time zone NOT NULL,

departure_time time without time zone NOT NULL,

distance_from_origin smallint NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT train_stations_pk PRIMARY KEY (train_no, seq));

CREATE INDEX train_stations_station_code_idx ON train_stations(station_code);

INSERT INTO train_stations

(train_no, seq, station_code, arrival_time, departure_time, distance_from_origin)

SELECT train_no, seq, station_code, arrival_time, departure_time, distance

FROM staging_trains;

When does a train arrive at the origin or leave from the destination ?

Trains do not arrive at their origin point or ever leave from their destination station but our data implies otherwise.

select * from train_stations order by train_no, seq limit 4;

train_no | seq | station_code | arrival_time | departure_time | distance_from_origin

---------|-----|--------------|--------------|----------------|----------------------

107 | 1 | SWV | 00:00:00 | 10:25:00 | 0

107 | 2 | THVM | 11:06:00 | 11:08:00 | 32

107 | 3 | KRMI | 11:28:00 | 11:30:00 | 49

107 | 4 | MAO | 12:10:00 | 00:00:00 | 78

The arrival_time at the originating station and the departure_time from the destination are set as midnight (00:00:00). These are, obviously, dummy values as there is no arrival time at the origin or departure from the terminating station.

Choosing the value of midnight gives wrong results for queries trying to find trains arriving or leaving at midnight, unless special care is taken.

Filtering arrivals at origin is simple, as seen in the second query below.

select * from train_stations t_s where arrival_time = '00:00:00' and station_code = 'NDLS';

train_no | seq | station_code | arrival_time | departure_time | distance_from_origin

----------|-----|--------------|--------------|----------------|----------------------

12310 | 1 | NDLS | 00:00:00 | 17:15:00 | 0

12562 | 1 | NDLS | 00:00:00 | 20:40:00 | 0

12622 | 1 | NDLS | 00:00:00 | 22:30:00 | 0

22412 | 1 | NDLS | 00:00:00 | 15:50:00 | 0

select * from train_stations t_s where arrival_time = '00:00:00' and station_code = 'NDLS' and seq <> 1;

train_no | seq | station_code | arrival_time | departure_time | distance_from_origin

----------|-----|--------------|--------------|----------------|----------------------

(0 rows)

Filtering departures from destination is slightly more complicated - remove the rows which belong to termination points or the maximum seq on a train’s route.

SELECT *

FROM train_stations t_s_1

WHERE departure_time = '00:00:00'

and station_code = 'NDLS'

AND (train_no, seq) NOT IN (SELECT train_no, max(seq)

FROM train_stations t_s_2

WHERE t_s_2.station_code = t_s_1.station_code

GROUP BY t_s_2.train_no);

train_no | seq | station_code | arrival_time | departure_time | distance_from_origin

----------|-----|--------------|--------------|----------------|----------------------

(0 rows)

My first instinct, after cursing the person who decided to use midnight as the dummy value, is to use nulls for arrival at origin or departure from destination. A null seems like a very reasonable choice here.

Before we can put nulls in these columns though, we have to drop some constraints.

ALTER TABLE train_stations ALTER COLUMN arrival_time DROP NOT NULL;

ALTER TABLE train_stations ALTER COLUMN departure_time DROP NOT NULL;

And then update our data.

UPDATE train_stations SET arrival_time = NULL WHERE seq = 1;

UPDATE train_stations SET departure_time = NULL

WHERE (train_no, seq) IN (SELECT train_no, max(seq) as seq

FROM train_stations

GROUP BY train_no);

Our queries are simpler now.

select * from train_stations where departure_time = '00:00:00';

train_no | seq | station_code | arrival_time | departure_time | distance_from_origin

----------|-----|--------------|--------------|----------------|----------------------

7517 | 3 | UDGR | 23:58:00 | 00:00:00 | 80

11079 | 24 | ANDN | 23:55:00 | 00:00:00 | 1704

15209 | 29 | BUW | 23:55:00 | 00:00:00 | 647

15909 | 16 | BPRD | 23:58:00 | 00:00:00 | 668

34754 | 13 | SJPR | 23:59:00 | 00:00:00 | 33

37291 | 4 | BLY | 23:59:00 | 00:00:00 | 8

40419 | 15 | PV | 23:59:00 | 00:00:00 | 23

43257 | 4 | PER | 23:59:00 | 00:00:00 | 5

52256 | 10 | NSA | 23:58:00 | 00:00:00 | 117

54057 | 20 | AILM | 23:59:00 | 00:00:00 | 73

79301 | 23 | SNYN | 23:59:00 | 00:00:00 | 218

96409 | 11 | OMB | 23:59:00 | 00:00:00 | 59

97437 | 9 | MTN | 23:59:00 | 00:00:00 | 10

97445 | 4 | BY | 23:59:00 | 00:00:00 | 4

97643 | 6 | CRD | 23:59:00 | 00:00:00 | 6

With this we can congratulate ourselves on a job well done, and yet something feels not quite right.

The problem with nulls

Take a step back and think about the very first action we performed to introduce nulls - we dropped not null constraints on the arrival_time and departure_time columns. A misbehaving program could put null values in these columns when that should never be the case and we just removed our safety net at the database level.

The second problem with playing fast and loose with nulls - a null should only stand for a missing or unknown value, not for data that can never exist.

Let’s split the train_stations table further so that we have seperate tables holding the arrivals and departures.

CREATE TABLE train_arrivals

(train_no integer,

seq smallint,

arrival_time time without time zone NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT train_arrivals_pk PRIMARY KEY (train_no, seq),

CONSTRAINT train_arrivals_fk FOREIGN KEY (train_no, seq) REFERENCES train_stations(train_no, seq));

INSERT INTO train_arrivals (train_no, seq, arrival_time)

SELECT train_no, seq, arrival_time

FROM train_stations

WHERE arrival_time is not null;

CREATE TABLE train_departures

(train_no integer,

seq smallint,

departure_time time without time zone NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT train_departures_pk PRIMARY KEY (train_no, seq),

CONSTRAINT train_departures_fk FOREIGN KEY (train_no, seq) REFERENCES train_stations(train_no, seq));

INSERT INTO train_departures (train_no, seq, departure_time)

SELECT train_no, seq, departure_time

FROM train_stations

WHERE departure_time is not null;

And now we can drop these columns from the train_stations table.

ALTER TABLE train_stations DROP COLUMN arrival_time;

ALTER TABLE train_stations DROP COLUMN departure_time;

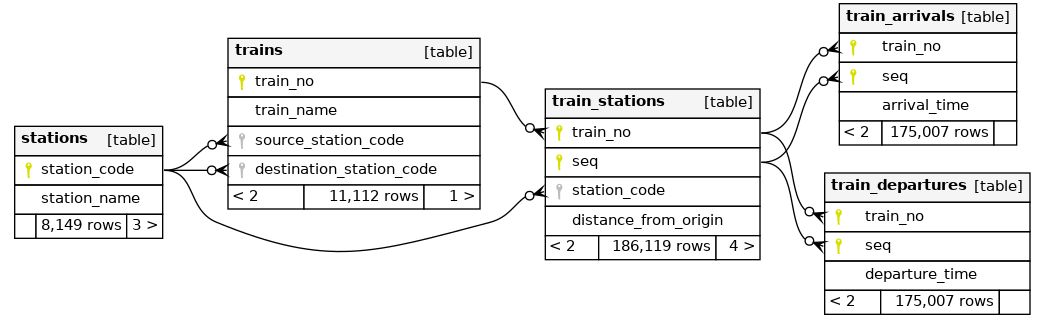

The datamodel

Getting to know the datamodel

What are the maximum, minimum and average halts for trains ? We only want to count the intermediate stations and not the source or the destination. The table train_arrivals does not have the source while train_departures does not have the destination station, so we should count the stations that appear in both the tables.

select min(halts), avg(halts), max(halts)

from (select count(*) as halts

from train_arrivals t_a

where exists (select 1

from train_departures t_d

where train_no = t_a.train_no and seq = t_a.seq)

group by train_no

) as foo;

min | avg | max

-----|---------------------|-----

1 | 16.6171550238264220 | 116

How long do trains stop at stations ?

In this case special care needs to be taken for trains where the arrival and departure span the dateline or midnight.

Let’s say a train arrives 15 minutes before midnight and leaves 15 minutes after midnight. Then just subtracting the departure from the arrival will not work.

select '00:15:00'::time - '23:45:00'::time as halt_time;

halt_time

-----------

-23:30:00

What we need to do is to subtract the arrival time from midnight, subtract midnight from the departure time and then add the two as in the case statement below.

select max(halt_time) as max_halt_time,

min(halt_time) as min_halt_time,

avg(halt_time) as average_halt_time,

percentile_cont(0.5) within group (order by halt_time) as median_halt_time

from (select arrivals.train_no,

arrivals.seq,

arrivals.arrival_time,

departures.departure_time,

(case when departures.departure_time < arrivals.arrival_time

then ('24:00:00'::time - arrivals.arrival_time) + (departures.departure_time - '00:00:00'::time)

else (departures.departure_time - arrivals.arrival_time)

end) as halt_time

from train_arrivals arrivals

join train_departures departures on arrivals.train_no = departures.train_no

and arrivals.seq = departures.seq

) as foo;

max_halt_time | min_halt_time | average_halt_time | median_halt_time

---------------|---------------|-------------------|------------------

04:00:00 | 00:01:00 | 00:02:31.564111 | 00:01:00

A not so final conclusion

We have our data nicely laid out in tables, but is this good enough to find trains between any two stations ?

Stay tuned for the next installment in this series to find out.